The Museo del Oro (Gold Museum) in Bogotá, Colombia, is filled with strange creatures imprinted into gold, the medium of choice of many pre-Columbian indigenous societies, such as Muisca, Quimbaya, Calima, Tayrona, and others.

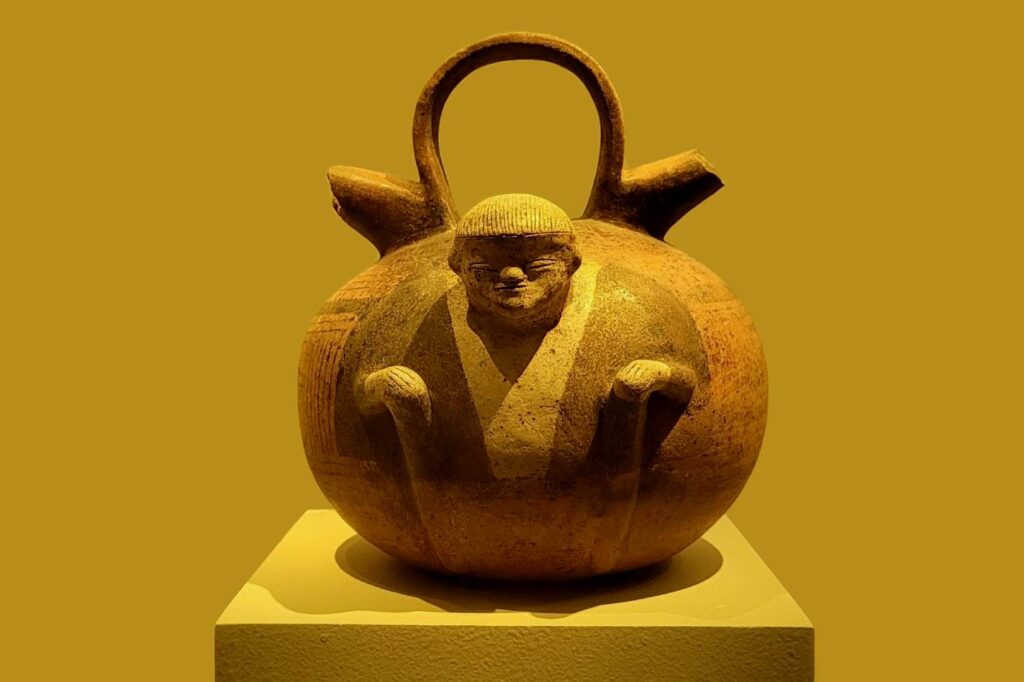

Tunjos were offering figurines made of gold or ceramics. They represented various deities, animals, humans, and other mystical beings with distinct cosmological meaning. The wide variety in forms, sizes, and details reflected the complexity of these societies’ spiritual narratives. The philosophy associated with shine and its ability to communicate with supernatural beings dictated the aesthetics by favouring materials and finishes for their reflectivity. Reflective surfaces like polished stones or pools of water were also used by ancient civilisations to observe celestial bodies and pinpoint the sun’s position for orientation during sea voyages.

In the worldview of Mesoamericans, the universe was divided into three realms. The upper and under worlds both sheltered ancestors, gods, and supernatural beings, and embodied contrasting but complementarity attributes like light and dark, masculine and feminine. While birds symbolized the upper world, creatures such as bats, caimans, and snakes personified the underworld due to their inclination to inhabit the openings of the earth. The middle world belonged to humans, jaguars, and deers.

Little distinction was made between humans and non-humans. Animals, plants, rocks and objects were all seen as individuals with their unique soul or spirit, all forming thriving communities by establishing homes, harvesting resources, engaging in communal living, and participating in dancing, just like humans do. Each being held its own world-view, shaped by its physical form that functioned like a malleable body-apparel (cuerpo-ropaje) readily worn or modified. By adorning themselves with feathers, ornaments, or body paint, humans can transition their body-apparel and transform into bats, jaguars, or fish, adopting the perspective of these animals and unveiling the mysteries of life and death.

On the other hand, Mesoamericans believed that parrots could transform into humans by learning to mimic human speech. Language and communication served as conduits for cultural preservation, transfer of knowledge, and social cohesion, and were seen as powerful tools. However, this transformation of parrots into humans also meant they could serve as substitutes for sacrificial victims.

In the indigenous Americas, caciques were believed to be descendants of divinities and powerful beings such as the jaguar. Their role was crucial in maintaining harmony between the human and spiritual realms. Staring directly at their face was forbidden, and their feet were never to touch the ground: they were carried on litters to indicate their elevated status. Even in death, their tombs were transformed into sanctuaries.

Colombian coca, known as coca novogranatense, was cultivated in the Andean region and kept in a container called poporo. Dried leaves were then combined with lime in the mouth to induce an intensified hallucinogenic haze that propelled priests into heightened states of consciousness. In this altered state, the line between the physical and spiritual realms blurred, allowing for communion with mythical entities.