At only 3,660 metres above sea level, the Salar offers a refreshing break from the bone-chilling climate of the Bolivian western Altiplano, where elevations range between 4,000 and 5,000 metres. Here, you are surrounded by a vast, flat, white expanse swept by uninterrupted winds. The extremely hard and reflective surface does not absorb any sunlight during the day, and temperatures drop well below freezing at night. Stays should be limited to a few hours, and preferably during the day, although some mad cyclists are known to ride across its surface and set up camp on its barren terrain.

Salar de Uyuni is the world’s largest salt flat, covering approximately 10,000 square kilometers with its immaculate, convex salt surface. It occupies the bottom of what used to be a prehistoric lake called Lago Tauca, which completely evaporated thousands of years ago. The flat is formed by layers of exogenous sedimentary deposits from a time when Bolivia was still submerged under the ocean. Millions of years ago, repeated cycles of cooling led rivers to accumulate mineral-rich waters in the lowest areas of the depression. These periods were followed by warming phases that caused the water evaporation, leaving behind a series of sediment layers.

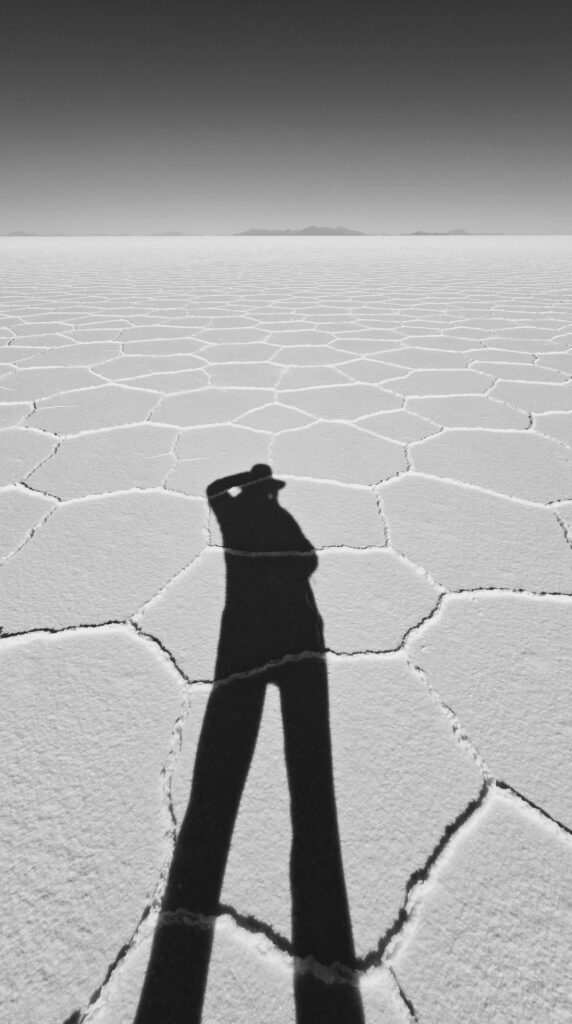

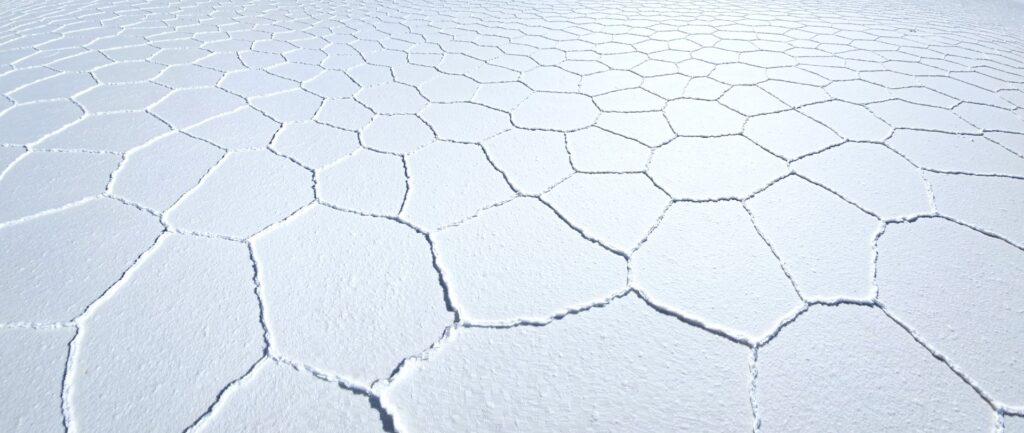

During the dry season, the salt crust becomes extremely hard, extending up to 120 meters deep. Beneath this crust, the salt remains saturated with water. The wide temperature fluctuations between day and night cause the crust to contract and expand, and cracks appear to minimize the elastic energy of the material. Interestingly, these cracks take the shape of polygons, mostly hexagons of 1 and 2 metres wide, whether the crust is a meter or a millimeter thick.

Why hexagons, and not square, triangle, or circle? Because hexagons are the most efficient way to relieve stress across a large surface area. They minimize the total crack length and distribute stress evenly, meaning it takes less energy to create and propagate the cracks.

Conversely, squares concentrate stress at their corners, making the material more prone to further cracking, while circles cannot tile up without leaving gaps. This is why hexagonal patterns are nature’s favorite and can be found in honeycombs, basalt columns, and drying mud. Variations in salt composition (specifically chloride and sulfite ratios) and environmental conditions cause the irregularities in the polygons.

When the top layer contracts, it draws up the underlying saltwater through the cracks to the surface. The groundwater then evaporates, leaving behind ridges of concentrated salts and other minerals along the cracks. This process is self-regenerating: no matter the damage done to the surface and the ridges—such as from car wheels—a pristine, flawless white surface with well-defined polygons will reappear as if nothing had happened.

During the rainy season from December to March, a thin layer of water accumulates on the salt flats, creating an otherworldly mirror-like effect and turning the entire area into a conductive field. This poses challenges for nearby lodging and driving, as vehicles must drive no more than 5 km/h to avoid draining the batteries.

The few dozen inhabitants of the Salar make a living by selling llama meat and extracting salt. The salt is then processed in Colchani, a village on the Salar’s eastern edge. Salt extraction is not a quick win: it involves hours of digging holes in the salt flats, where the salt burns the skin, the sun damages the eyes, and the wind weakens the spirit, all for just a few bolivianos. In the past, communities exploited the salt primarily for trade with other indigenous communities. Caravans of llamas would carry salt as far as Tarija, returning with maize, coca, and other goods. The llamas wore leather shoes and visors to protect them from the salt and the glare of the white surface.

Salar de Uyuni is also home to the world’s largest deposit of lithium, today’s precious mineral that powers modern technology, such as the rechargeable batteries of electric cars and smartphones. This prompts the Bolivian government to start extraction projects, despite the consequences for the fragile ecosystems. Lithco (Lithium Corporation of America) currently operates extraction projects in Argentina’s Hombre Muerto salt and Chile’s Atacama Desert. They had to leave Bolivia due to opposition from the locals, who were against the new pillaging of national resources.