Area: 53,588 km²

Elevation: 3,700 m

Population: 494,500

Date visited: From Sunday evening, July 28 to Saturday morning, August 3, 2024. The strike began on Monday, July 29, and ended on Friday morning, August 2.

Oruro (Bolivia) is dusty, elevated, and known for its mining and carnival. Although I was too early for the famous carnival of February, I got to experience another major event that should be added to the city’s attractions: the road workers’ strike.

A brief stopover in Oruro on the way to La Paz turned into an extended stay. This wasn’t due to the city’s mesmerizing charm but rather because the city had been paralyzed by blockades a day before my intended departure.

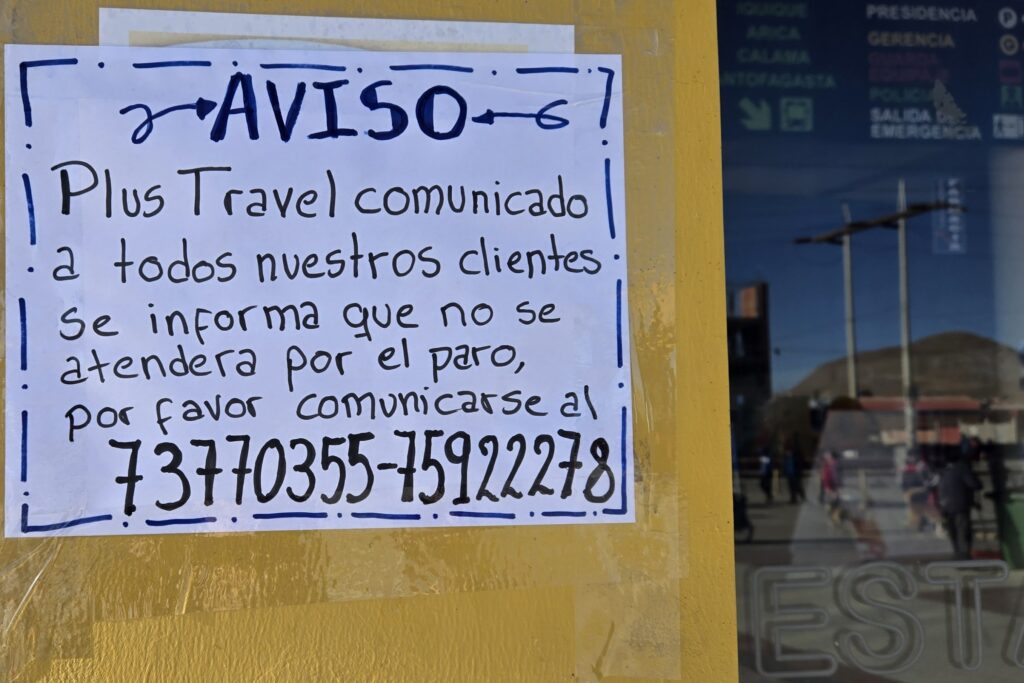

A diesel shortage and a lack of dollars led drivers to protest, resulting in the cancellation of all departures and the eventual closure of the bus station. Initially affecting major roads, the blockades quickly spread to secondary routes.

The efficiency of the blockades was striking. The workers’ impressive organization skills and utmost seriousness could be seen in the precise alignment of thousands of trucks, buses, and vans to obstruct as much passage as possible. The protest extended to Sucre, La Paz, and Cochabamba, becoming nationwide. When it comes to getting something from the government quickly, we could all learn something from the Bolivians.

Faced with this reality during my daily excursions, I grew pessimistic about the disruption being untangled soon and expected to delay my stay indefinitely. Little did I know, everything would return to normal overnight.

It was Tuesday morning around 10:30. I walked from my hostel to the bus terminal, a 45-minute trek under the sun. Unaware of the situation, I found an eerily calm atmosphere inside the terminal. I soon hit a dead end: no one was at any of the bus company counters. An information attendant finally informed me that all departures were canceled for the day. Tomorrow? Not sure. Service might resume in the evening, but who knows.

I could have been stuck in Sucre or Cochabamba, cities with much more charm where I would have gladly stayed longer. But fate decided I should remain in Oruro, a city characterized by sandy, dusty roads, trash piles, packs of whacked stray dogs, urine smells, and endless rows of unfinished brick buildings. Apparently, two days weren’t enough to appreciate or understand Oruro’s charm; in my posh hotel room, I had plenty of time to uncover the hidden gems beneath the debris and construction site atmosphere.

I booked a room in a hotel across from the bus station in a vacant lot. “Oruro Inn” was written across the yellow building, dominating the wasteland. Luckily, the interior was luxurious, and the price fit my stretched budget (I eventually bargained the rate down to 100 bolivianos a night). Considering the quality of the hotels in the central area, it was a very good deal. My room on the 3rd floor had full sunlight and an uninterrupted view of the urban desolation below.

The Secret Beauty of an Ugly City That Defies Logic

Founded in 1606 as a silver mining center, Oruro is Bolivia’s fifth-largest city by population, following Santa Cruz de la Sierra, El Alto, La Paz, and Cochabamba. Named after the native Uru-Uru tribe, Oruro has experienced economic rise and fall due to its dependence on mining industries.

Once the silver mines were exhausted, Oruro became a crucial trade hub with Chile, transporting goods for export by road to the Pacific port of Iquique and by rail to Antofagasta. Simply put, it became the perfect place for blocking roads to make demands.

However, tourists are more interested in Oruro’s carnival, the second most significant in Latin America after Rio, celebrating the Virgin of the Mines with the Dance of the Devils (Diablada).

At the bus terminal Tuesday evening, people waited on the polished floor, diligently maintained by the cleaning staff, who gave side-eyes at anyone daring to step on their work. On the giant screens, Croatia and Korea competed in women’s judo at the Paris 2024 Olympics. The modern space, with its circular two-story layout, mezzanine, and geodesic dome, contrasted with the chaos at the perimeter, where dozens of bus companies competed for attention.

Since Wednesday morning (or possibly Tuesday night), the terminal remained closed. Where do all these people and families with their luggage sleep in the freezing night? Some still waited outside in the morning, sitting against the entrance door, armed with blankets.

The blockades intensified day after day, with stones and ropes added to prevent even motorcycles and cyclists from passing. I was told that motorcycles trying to escape received sticks in their wheels—dangerous tactics, but the strikers were relentless.

The city’s urban layout is incomprehensible, built on flat terrain between mountains and encircled by a beltway.

It is Thursday, August 1. Intense sun, hot day, no clouds—typical of the Altiplano. Aside from the dust and the lack of shade, navigating the city was a challenge; the shortest distance between two points was never a straight line. It was a half-curve, a sharp turn, a diagonal, or a couple of U-turns at dead ends. The city felt like a fortress designed to confuse visitors—a perfect defense mechanism.

On the positive side, walking Oruro’s traffic-free streets, except for some motorcycles and bicycles, was a breath of fresh air. Quiet, gasoline-free air, no fear of being hit by a taxi—not something often experienced in these parts of the world. But how long before the lack of supplies and public frustration set in? So far, the locals seemed used to it.

I walked to the airport, where both main access roads were blocked by airport vans. Two armed men guarded the gate of the airport, but did not block the access. One confirmed that the airport was operational. Surprisingly, despite the desolate atmosphere, the airport functioned normally. Inside, only two people were present, including a Boliviana de Aviacion boarding attendant. He assured me no flights were canceled, but all were fully booked, making last-minute tickets impossible. I had an exit plan, in case things worsened…

I then had lunch at a local charquekaneria to try Oruro’s typical dish: sun-dried, shredded llama meat, large white corn kernels, whole potatoes, and a slice of fresh feta-like cheese, all for just 13 Bolivianos. It was tasty and filling. The walls of the small diner were filled with images of unsuspecting llamas sporting cute hairstyles.

The hidden gems of Oruro, as I should have suspected, were its authentic local flair and the resilience of a town that lives despite being underestimated. The town thrives with regular friendliness and satisfying meals. Most of all, its people keep on living in uncertain times, stricken by regular strikes that nonetheless impact their livelihoods.