One thing was sure: if I was going to visit Paraguay, I had to go to Filadelfia. That strange German town, a dot in the blank space of Google Maps. A place I knew nothing about and began to trigger all kinds of imagery from my unconscious mind. I needed to see it for myself to confirm it was real and to understand how it could even exist. As I investigated the deep corners of the web for information, my hope began to fade; this was not going to be a walk in the park. I had little control over the outcome, but it could have been worse.

Despite being in a remote region of one of the poorest countries in South America, the town felt safe and well cared for. I certainly wasn’t expecting the most Europeanized, well-stocked supermarket I had ever seen in all of South America—somewhat disproportionate for a population of just 15,000. I also didn’t anticipate the incredibly helpful and friendly locals who offered me a lift as I walked along the highway, or the diverse and serene tri-lingual community speaking German, English, and Spanish fluently. Then there was the five-star hotel where I was dropped off, boasting surprisingly affordable rooms that, unfortunately, were all booked for the night.

Still, I enjoyed the refreshing lobby as a refuge from the heat and desert dust outside. I drank a refreshing cappuccino at the bar and after moving to a cheaper hotel a few blocks away, I experienced the eerie atmosphere of walking the streets at night, free of garbage and stray dogs. A fine mist of sand particles floated in the air and created a comfortable haze.

Crossing South America’s “Green Hell”: Where the Amazon Turns into a Dry Forest

The Gran Chaco is the most sparsely populated area in South America, covering 1.1 million square kilometers and spanning four countries: Paraguay, Bolivia, Argentina, and Brazil. A third of it makes up half of Paraguay. While I’ve seen my fair share of subtropical landscapes, the Chaco is unlike anything else: a surreal blend of environments that you don’t usually see together—desert and rainforest.

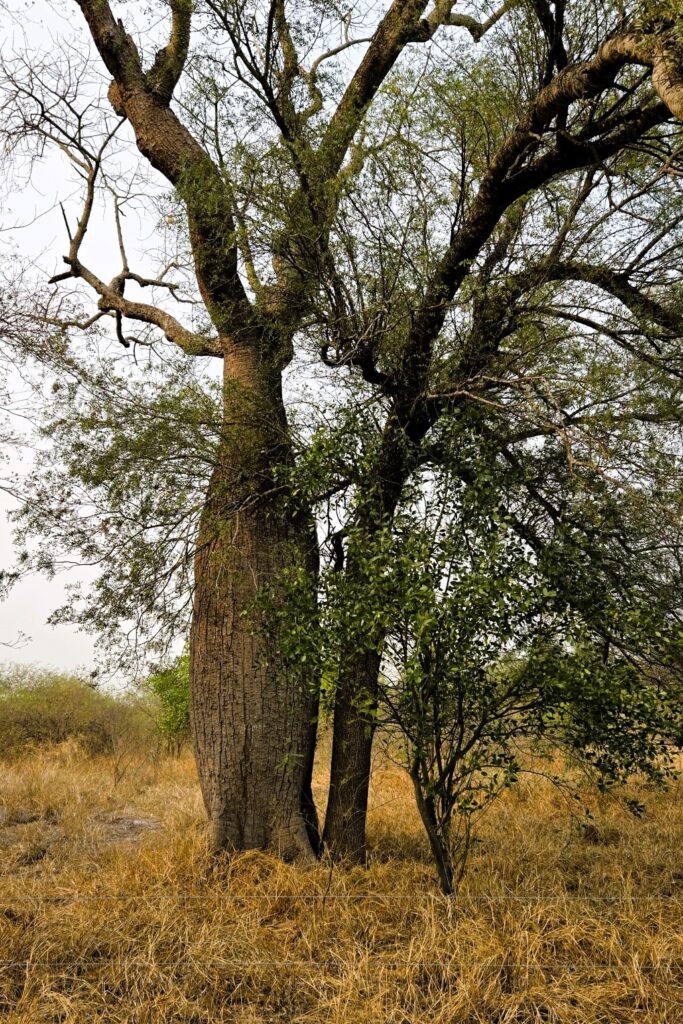

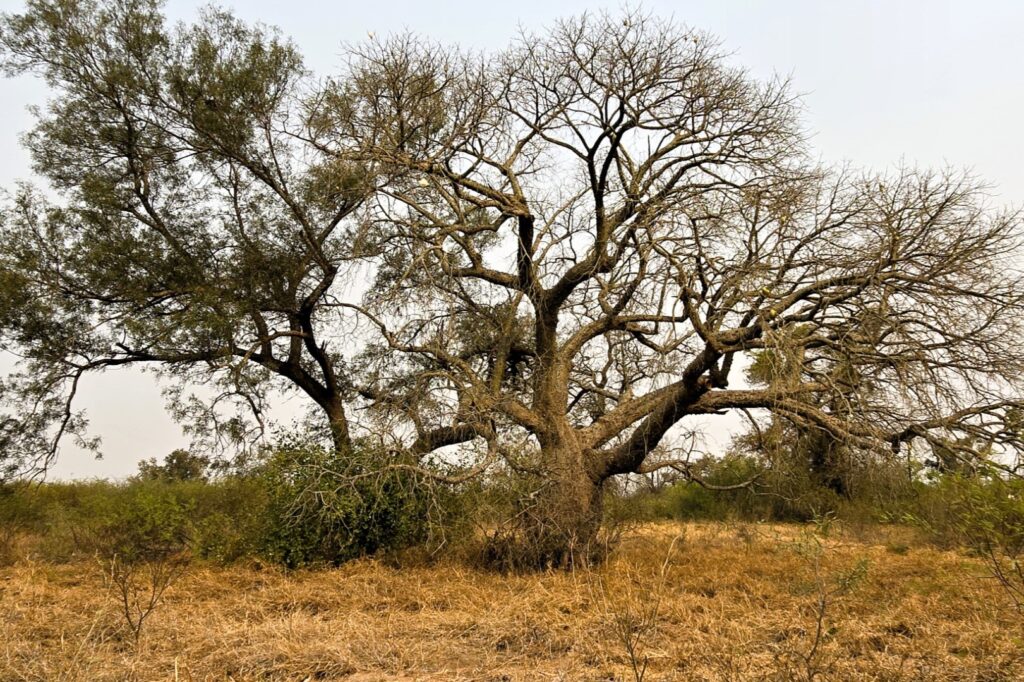

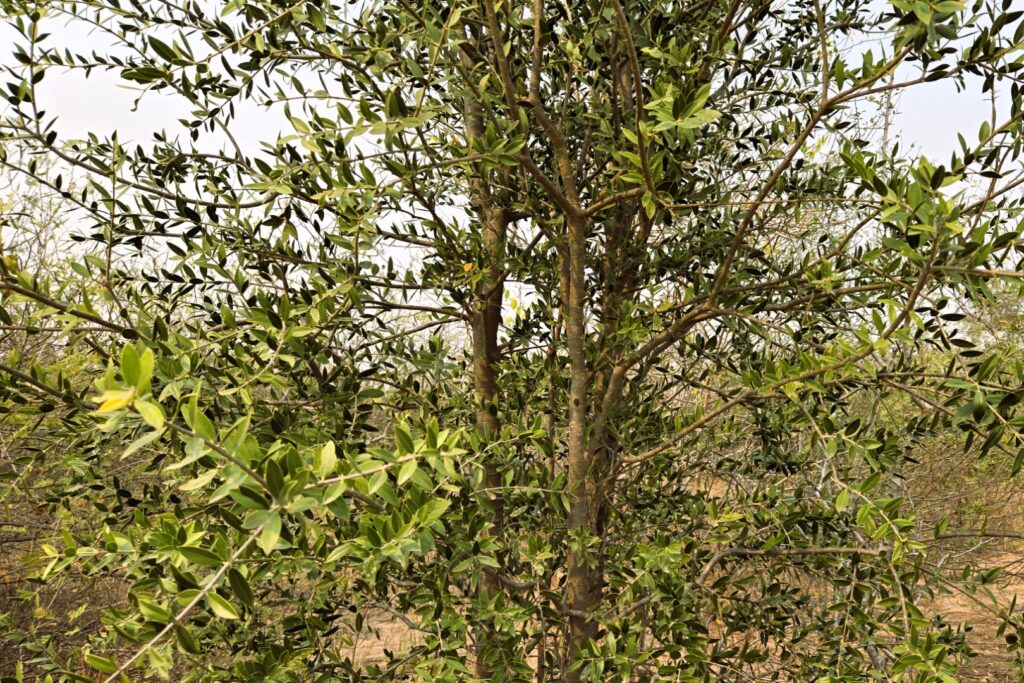

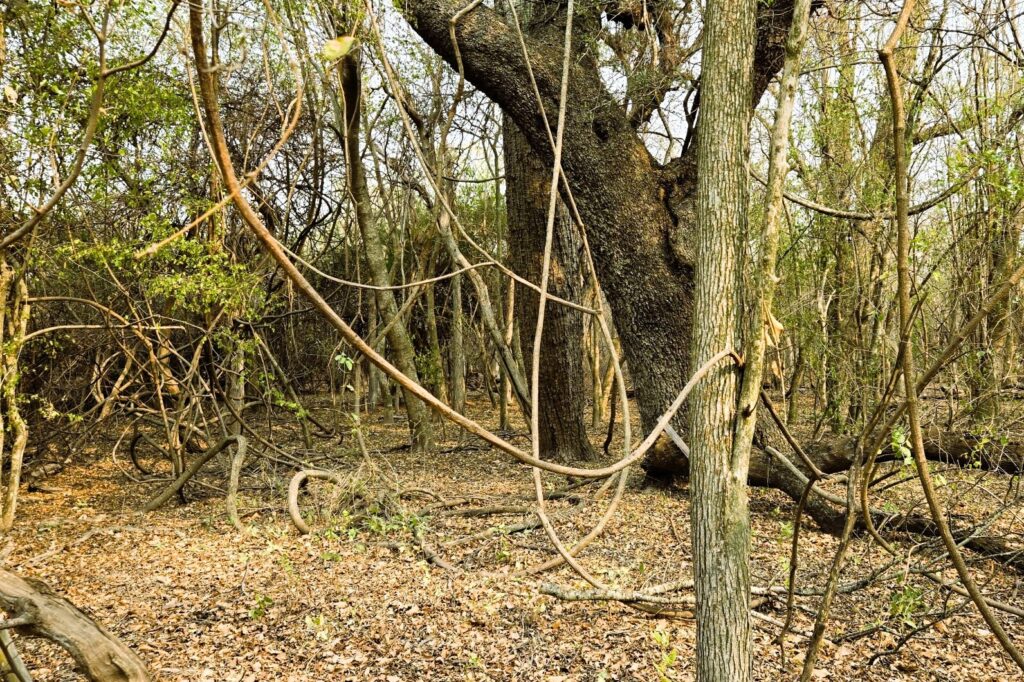

Known as the “Green Hell” for its dense, thorny vegetation and extreme conditions (with summer temperatures often rising above 40°C), the Gran Chaco is one of the continent’s toughest environments. Yet, it’s home to a surprising variety of wildlife. Despite the region being mostly dry, patches of rainforest can still be found away from rivers, in depressions where rainwater collects. Changes in the soil composition are reflected in the vegetation: the east is characterized by clusters of trees and shrubs scattered among tall grasses, while the west is blanketed by a dry forest of spiny bushes and low trees.

Endemic trees have adapted to these dry conditions. Quebracho trees, for instance, produce wood that is extremely hard and resistant to rot. These trees play a crucial role in supporting the growth of grasses in the savannah below. Unfortunately, most quebracho trees have been cut down and burned to make space for cattle, putting them at risk of extinction. The Palo Borracho, also known as the drunken tree, looks bloated with its pear-shaped trunk, which stores water. The softer, lighter wood has a spongy texture, and the pink or white flowers produce cotton-like seeds.

A German Settlement in the Desert

In the middle of it all lies Filadelfia, a mirage in the Chaco desert. What makes this settlement even more unlikely are its residents: fair-skinned, blonde Germans. Back in 1925, German Mennonites fled persecution in Russia and ended up settling here in the remote Chaco. They made a deal with the Paraguayan government, which was eager to establish a settlement in the vast Chaco region that did not yet have a defined border with Bolivia. Not long after, the Chaco War broke out between Paraguay and Bolivia from 1932 to 1935, the longest territorial war in South America.

During the conflict, the Mennonites stayed true to their commitment to non-violence, offering food and drink to soldiers instead of fighting. After the war, Paraguay gained new land, and the border with Bolivia was finally settled. However, the Mennonite settlement remained isolated, with no roads connecting it to the rest of the country. Initially, the government provided oxen and carts to transport goods from the train station, but these proved ineffective in the desert terrain. Over time, they upgraded to sturdier wheels and horses, and eventually, the Trans-Chaco Highway was built—though it passed 14 kilometers away from the colony.

Today, many young Mennonites leave for Germany or Canada to escape the intense heat, and new immigrants are drawn in by the government’s relaxed policies on settlers. There are three main Mennonite colonies thriving in the Chaco: Loma Plata, founded in 1927; Filadelfia, established in 1930 by refugees from the Soviet Union; and Neuland, founded by Ukrainian Germans in 1947.

While there are other Mennonite communities in Paraguay, the ones in the Chaco are especially known for their resilience in this “Green Hell.” What started as a self-sufficient community has grown into a commercial success, with their cooperatives supplying much of Paraguay’s dairy products. Over time, the Mennonites have developed sustainable farming practices, particularly in cattle ranching, that are well-suited to the Chaco’s tough environment.

The settlements have also evolved into a culturally diverse community, with indigenous groups like the Nivaclé and Guaraní living nearby, and German and English being widely spoken despite the isolation.

How to Get There

Filadelfia lies at the center of the least populated part of Paraguay, surrounded by the vast Gran Chaco desert shared with Bolivia and the Pantanal wetlands shared with Brazil. It’s as remote as it can get. It’s not a surprise that the city often goes unnoticed, and the lack of transportation options is a clear indicator of this.

If you’re thinking of crossing the border from Bolivia, be prepared for an uncertain journey: it’s neither easy to plan nor straightforward. Border crossing is never a consistent process, and you’ll get dropped at an intersection along the Trans-Chaco Highway, leaving you with no choice but to walk the 14 kilometers under the midday sun and hoping to get a lift along the way. It’s still easier than the reverse, we’re you’ll have to catch the bus at the same intersection in the middle of the night.

Following my experience to stay in populated area to have all chance on my side, I decided to start my trip from Santa Cruz, Bolivia’s largest city, for more convenience and flexibility—a decision I didn’t regret. You only have two bus companies to choose from, and they don’t run daily. I picked Rio, which worked out fine, but I was just relieved to find a direct option and didn’t think to haggle over the price—big mistake. It seems they overcharge tourists.

The waiting area at the bus company wasn’t great, but I managed to snag a chair, which was lucky since the bus was two hours late. It was a single-decker “cama” bus, which doesn’t mean 180-degree reclining seats—just fewer passengers and more space per seat. The bus was half-full, with around 15 passengers total, and the seats were more comfortable than your average bus. It was clean, and each seat had a USB port. We made a few mandatory stops along the way, including at a coca leaf store for refills. During the night, I was waking up every hour at night, trying to find a position that wouldn’t leave me numb.

Another mistake I made was thinking I could easily find Paraguayan guaraní in town before leaving Bolivia. Don’t count on it. Not one of the ten places I tried had any. I guess Paraguay isn’t high on Bolivia’s travel list. Thankfully, some opportunistic street vendors near the border—and a “cambio lady” who hopped on the bus—were more than happy to exchange bolivianos at a painful, non-negotiable low rate. Make sure you spend all your bolivianos before entering Paraguay, as you won’t be able to exchange them afterward. I used up some for a drink and a chicken meal before departure, along with the annoying $2.50 bus terminal fee, and exchanged the rest before crossing the border. Once in Filadelfia, you can easily withdraw cash from the ATM at the town centre.

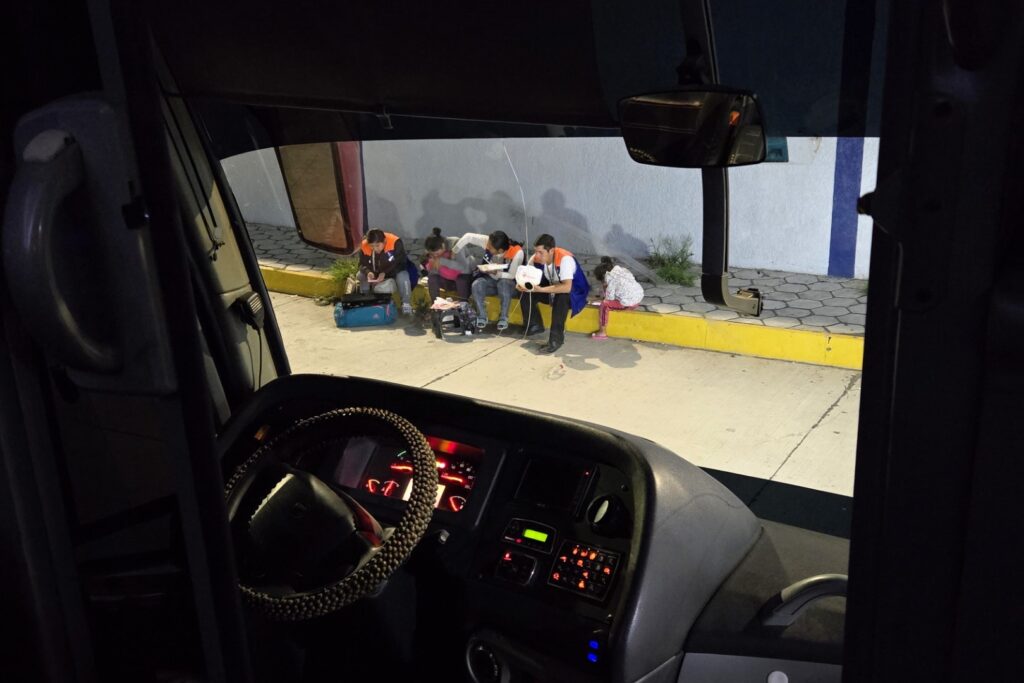

However, despite leaving two hours late, we arrived before the checkpoint opening time of 7:30, which made me question the whole logistics. On the bright side, the immigration process was fairly smooth, though it involved a long wait. Both countries share a surprisingly modern station with plenty of bathrooms but not much else. On the Paraguayan side, there are two more checkpoints (because, why not?), and at the last one, you’ll have to get off the bus with your luggage for another round of bag patting and pocket searching.

The bus ride and walk tour of Filadelfia, Paraguay