I just spent a full month living in Costa Rica – not on vacation, not hopping between beach resorts, but actually living there. I arrived on May 1st, right at the beginning of the rainy season. Since I came straight from Medellín, I’ll be using Colombia as my comparison baseline to evaluate the day-to-day life in Costa Rica.

* The dollar ($) is the Canadian one (CAD), and prices are based on the current 2005 conversion rate

Costa Rica is the tropical poster child for northern vacationers, the OG influencer destination. But honestly, I wasn’t immediately blown away. It had to grow on me. Like with any destination, the real country reveals itself once you get beyond the tourist zones. That’s where you’ll find the real charm: the people, the everyday life, the moments that aren’t staged for show. Still, it got me thinking: why does everyone rave about Costa Rica?

It a sizable place (about half the population of Cuba) and it feels like an island with its extensive coastline. It tends to steer clear of the headlines, thanks to its political stability, and it’s the ultimate “green guilt” getaway due to its ethical gold star and national park system that crams 5% of the world’s biodiversity on just 0.03% of the Earth’s landmass.

But when it comes to living cost, it’s a different story. Costa Rica is officially the most expensive country in Central America, and possibly all of Latin America. A month here cost me about the same as a month in Canada (yep, that expensive), and around 66% more than in Colombia. And that was without doing much — no bars, no restaurants (aside from the occasional soda for basic survival), no tours or site visits… except for two weekend getaways to La Fortuna and Manuel Antonio.

Still, I traveled on a budget, using bus transport that cost me about $10 USD round trip for both destinations. In La Fortuna, I stayed a couple of nights in a jungle campground with a rented tent and mattress for $10 USD a night, which was fantastic. In Manuel Antonio, a beachy jungle strip on the Pacific, I scored a same-day, last-minute deal: a massive double room with a private bathroom, large terrace, and breakfast included, all for the same price as a stuffy, smelly dorm bed ($20 USD a night).

My monthly spending also included the flight from Colombia to San José, plus a splurge on a 3-star hotel for the first two nights (I wanted a pool, but it wasn’t worth it). I took a taxi from the airport due to my late-night arrival, and grabbed Ubers when switching Airbnbs (twice). The rest of the time I got around by bus and urban train, with the rides costing around 500 colones (averaging $1 USD). Fun fact: each bus had its own fare written on the dashboard. I’m still not sure if that’s based on the route, the driver’s mood, or the condition of the bus. They take cash, though they’ve also started taking payment by local bank cards.

La Comida Locale

Food prices are absurd—especially, and ironically, for locally grown mangos, papayas, and avocados, which often cost as much as in Canada, if not more. Imported beer from Portugal or Germany is cheaper than the local one. A small cappuccino at Starbucks goes for US$8 (₡2,800), the price of a full meal, but it’s one of the few places where you can actually work comfortably.

To keep costs down, I hunt for discounts in supermarkets as I would back home in Canada. MaxiPali has the lowest baseline prices, but Auto Mercado, a higher-end store, offers better discounts, like prepared meals for $5 if you shop in the evenings.

The cheapest meals are at local sodas (small eateries), starting at ₡3,200 but twice what you would pay in Colombia. For this price, you get the standard plate: rice, beans, a tiny salad, fries, a portion of meat, and a sugary juice. No soup. That said, the quality, especially that of baked goods, is generally better than in Colombia. A bean-and-meat empanada costs about $3 and is filling enough to count as a meal. Unlike in South America, but much like in North America, breakfast is the heaviest meal here: gallo pinto (rice and black beans), shredded meat, a neon-pink sausage of dubious origin, a block of fried cheese, and simple white bread (baguette).

Rock-bottom dining: the sodas

Typical breakfast: pinto (arroz y frioles), fried cheese, sausage, shredded meat, and white bread.

₡2,900 / $7.70 (US$5.60)

Typical lunch: pinto, salad, French fries, and a protein (fish), served with a sugary-creamy drink.

₡3,500 / $9.40 (US$6.80)

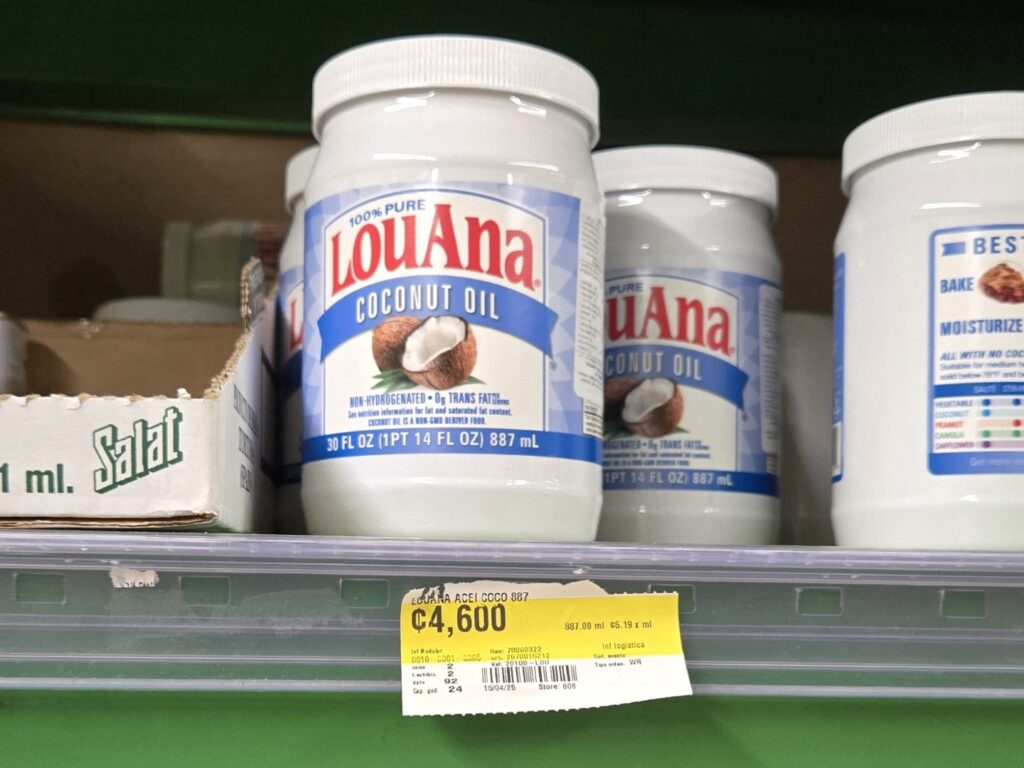

What You Can Expect to Pay at Grocery Stores

Free water, Flexible living

One perk is that potable water flows from every tap and tastes better than in Colombia (less chlorinated). Costa Rica and Colombia are among the few Latin American countries with a fully potable water system.

When it comes to temporary housing, there’s more variety at a better quality-to-price ratio than elsewhere in Central America. The slightly higher level of infrastructure makes short-term stays more appealing. But what you save on rent, you lose on food.

Weather, navigation and safety

Temperature-wise, I got to keep my lovely Colombian weather, the cool, mountain kind, by settling in the suburbs of San José, around 1200 meters altitude, and even climbing further up the volcano slopes in Coronado de San Isidro.

Despite being only an hour away from Medellín by air, the fauna and the bird chorus are quite different. Costa Rica is much tamer on the bug front. Aside from ants trying to eat your feet if you stand still too long, there weren’t many annoying bugs, which was a pleasant surprise–especially compared to Brazil and Argentina where I served as a mosquito buffet for most of my time.

Navigation-wise, Costa Rica is small and kind of island-style, with lots of coastline and a central region stacked on volcanoes. San José spreads like an oil stain and the road infrastructure is patchy and shaped like a star – if you want to get from suburb A to suburb B located right above, you’ll still need to go all the way back to the city center.

Add to that a maze of cul-de-sacs and dead ends, and you quickly learn that the fastest route between two points is a zigzag. This might partly explain why everything is so expensive: delivery must be a logistical nightmare. This goes for the rest of the country, with San José as the central node.

Outside the city, most roads are made for cars only. Sidewalks are rare and bike lanes are basically non-existent. Between the racing drivers and impatient truckers, walking or cycling often feels like asking for trouble. For comparison, Cuba was way more friendly to slow travelers.

In terms of safety, Costa Rica feels pretty similar to Colombia. The central parts of San José can feel sketchy at night, especially when walking between bus terminals that are outside the busy zones. That said, once you’re out in the suburbs, it’s quiet and secure, and travelling by bus is totally safe even late at night.