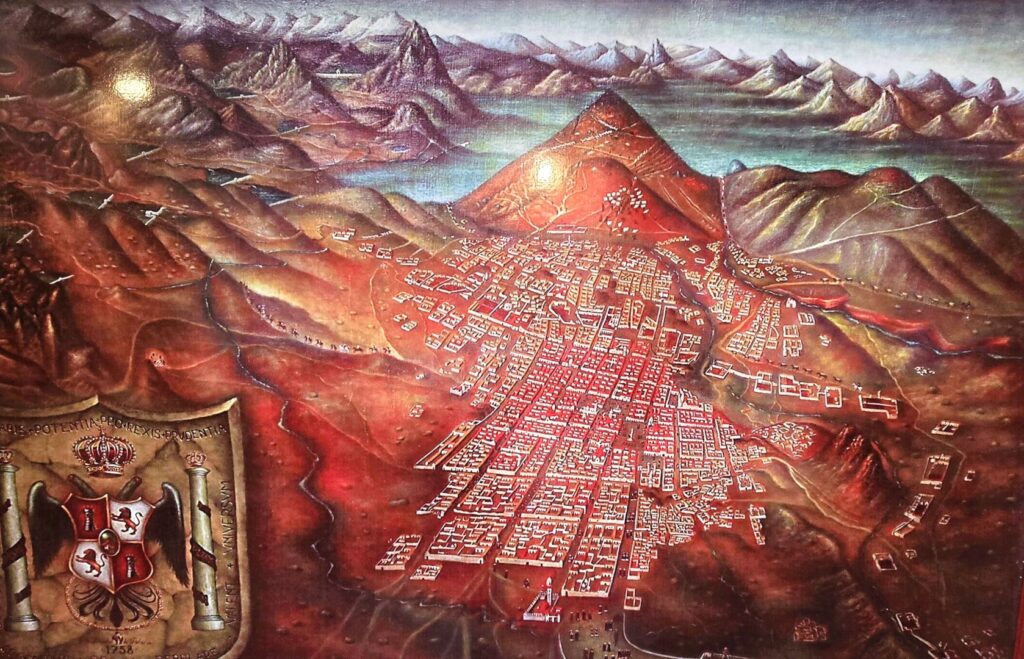

Potosí rests on a barren central altiplano at nearly 4,100 metres in altitude, tormented by icy winds and arctic nights. Despite its remoteness, its centre is a frozen tableau of colonial architecture, with baroque frosted churches and convents reflecting a past explosion of opulence and indulgence. The old city is built on a slope that drops abruptly to the new city, and its streets are purposely designed to twist and curve to cut the wind. The thin air in these narrow streets is filled with a sense of sadness, echoing a tragic history. To the south looms Cerro Rico, a cone-shaped mountain stained by centuries of mining waste and perforated with so many mines that it threatens to collapse.

This peculiar city owes its existence to the world’s largest silver deposit, nestled within Cerro Rico. In the early 16th century, after the conquistadors seized the immense treasure from the Incas, Potosí quickly became an imperial city and a vital industrial complex, producing about 60% of the world’s silver. In the 17th century, it even surpassed Paris in size and significance. While Cusco and Machu Picchu were the epicenters of the Incan empire, Potosí was the heart of the Spanish empire. The exploitation of the city’s minerals is believed to have fueled the economic development of Renaissance Europe. However, this wealth came at the cost of an estimated 8 million indigenous forced laborers and African slaves who died between 1545 and 1825.

Although mining output began to decline in the early 19th century, the growing demand for tin (étain) in the 20th century, driven by the electronics industry, helped sustain the local economy. Since 2004, the number of ore processing plants has tripled, and many miners returned to the dim passageways to rework old silver mines for less valuable metals. The working conditions remain miserable as they were centuries ago, with silicosis—a deadly lung disease—and occasional cave-ins significantly reducing life expectancy. Yet, the miners earn a better living than early-career teachers and take great pride in their traditional line of work. Chewing a mouthful of essential coca leaves before entering the mines helps keep fatigue, hunger, and exhaustion at bay.

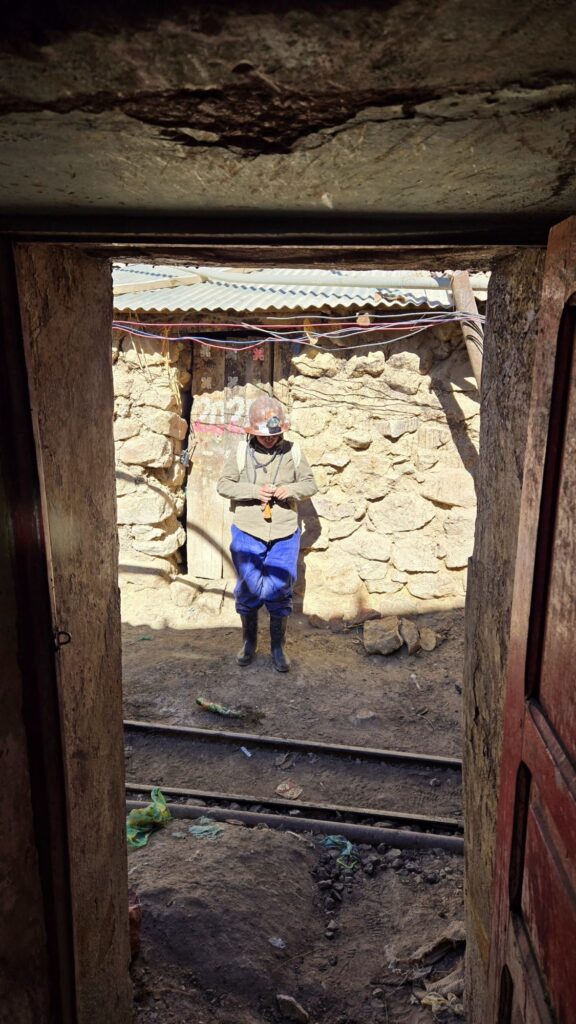

However, the interior of the mountain is not as lifeless as it seems. Deep within the mines reigns El Tío, the Lord of the Underworld. El Tío is the Quechua pronunciation of “El Dios”, as the language lacks the “D” sound. Although the entity is derived from the God of Catholicism, it shares little resemblance with it. El Tío remains confined to the mines due to condemnation from the Catholic Church. Conversely, Christian symbols are not allowed inside the mines: the Underworld is El Tío’s domain. To appease this devil-like spirit, who is responsible for both protection and destruction, miners bring offerings like cigarettes, coca leaves, and pure alcohol to the many shrines within the mines.

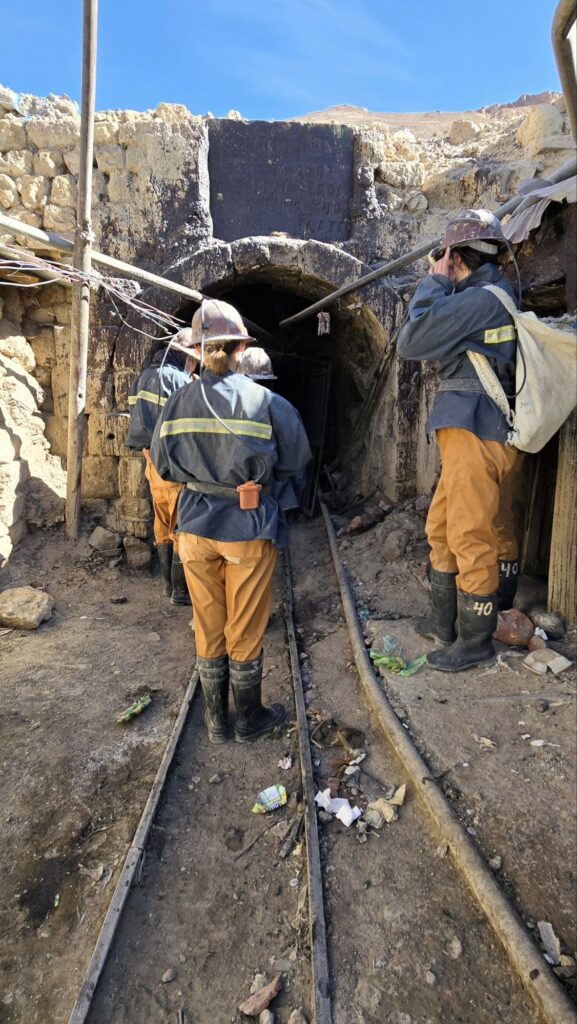

Visiting the mines is not for the faint-hearted. Claustrophobia can be psychologically challenging, but the thin air mixed with dust and gases can make breathing difficult.

The three-hour tour costs 130 bolivianos (18$US or 26$C) and includes two hours inside the mines with opportunities to talk to the miners at work. Due to the confined spaces, groups are limited to eight people. Our group consisted of six tourists, two young staff members from the tour agency responsible for our well-being, and an experienced guide. The tourists included a couple from Colombia, a Greek, a German, and a Swiss. Both the staff and the guide were familiar with the mining conditions and clearly enjoyed the trip, a sentiment not necessarily shared by us newcomers.

No special provisions were made for tourist comfort, which, in a way, spared us from feeling patronized or pampered.

As we had to roll in dust, fumes, and muddy water, we were equipped with overalls, jackets, boots, headlamps, and helmets to protect against frequent head bumps. After gearing up, we visited a miners’ shop to buy mandatory surgical masks and gifts for the miners: coca leaves, black-tobacco cigarettes, pure cane alcohol, carbonated drinks, and even dynamite sticks. Yes, dynamite. Despite cooperatives overseeing the operations, miners have to purchase their own equipment.

A few minutes after entering the mine, we paused at the shrines to light a large cigarette for El Tío and pour alcohol on different parts of his body, as he and the supernatural forces are in charge of security down there. It seemed to work, as we avoided many dangers like the lack of breathable air, falling stones, and runaway trolleys. The pure alcohol that remained is mixed with water to create artisanal whisky.

Although the entrance of the mines appears quite sturdy, with stone linings dating from the colonial era, it soon begins to deteriorate as we go deeper. With five centuries of tunnels digging, nearly 100 kilometers of underground passages, and numerous sinkholes (some up to 50 metres wide), shaken daily by explosions, the mountain has been officially deemed unstable and on the verge of collapsing since 2014.

Despite the entrance being over 4,000 metres above sea level, the temperature inside the mines can reach 40°C. The tunnels narrow, and the ceiling lowers as we progress, forcing us to bend sideways and sometimes crawl through connecting passages, stirring up dust and gases in the already thin and rancid air.

After about an hour of walking and crunching through debris, I began to worry about the location of the nearest exits. To further test our trust, we descended to a lower level via a winding, narrow connecting passage that disturbingly narrowed to the size of a pipeline halfway down. However, the confidence of our guide kept us moving forward. No one in our group required assistance, but I could easily imagine the panic some might feel; apparently, every tour has one or two people who want to leave within the first 10 minutes.

Up to 15,000 miners still work in Cerro Rico, including many children. More than 30 mining cooperatives serve as the main organizational structure for these miners.

Hay algunos que, habiendo entrado sólo por curiosidad a ver aquel horrible laberinto, han salido hoy descoloridos, castañeteando los dientes y sin poder pronunciar palabra; no han sabido ni cómo ni hacer referencia a los horrores que hay allí.

There are some who, having entered only out of curiosity to see that horrible labyrinth, have come out today robbed of colour, chattering their teeth and unable to pronounce a word; they have not known even how to describe or even refer to the horrors that are in there.

Historia de la villa imperial de Potosí, by Bartolomé Arzáns de Orsúa y Vela