Traveling north from Argentina, I embarked on the legendary 4-day, 4×4 journey through Bolivia’s most remote high-altitude deserts. Starting from Tupiza and ending in Uyuni, we passed abandoned villages, bizarre rock formations, arid badlands, and stared at the colorful toxicity of lagoons. In 20 years of traveling, I’ve rarely set foot in a place so surreal it could belong to another world.

Table of Contents

Booking a tour to the Salar de Uyuni turned out to be much easier than my outdated guidebook had suggested. Prices were largely standardized across agencies, and most hotels had their own affiliated tour offices, so there was no need to search all over town unless you really wanted to.

In normal times, several tours depart daily; but due to recent political unrest in La Paz, most tourists had scattered away, and the atmosphere was unusually quiet. During low-traffic period, tour operators collaborate to fill their 5-passenger jeep quotas, so the agency you book with might not be the one you end up touring with.

Most travelers start their tours in Uyuni anyway, which is closer to La Paz. But Tupiza, where I happened to be, is a less popular departure point that offers more captivating landscape viewing.

To avoid overthinking my options, I found a good enough hotel with a good enough tour office and booked on the spot. Though I probably should have spent more time clarifying the pricing and inclusions, the tour ended up being one of my most memorable experiences.

The main take away:

What makes or breaks a tour is the group of people you travel with. But given the human capacity to surrender to awe, even the most indifferent or difficult travel companions might become tolerable. Our group consisted of five passengers plus the driver. Despite the absence of proper roads, the vehicle was surprisingly comfortable, which was a good thing given the long hours we spent driving.

Our driver wore many hats: guide, weather expert, entertainer, DJ, photographer, and occasional herder when one of us wandered too far. Fortunately, he spoke a version of Spanish adapted for “gringos.” Meanwhile, our mama-cook followed in a separate vehicle and prepared rustic buffets that turned out hearty and delicious.

Traveling in June and July felt like winter camping: no showers for four days and wearing the same five layers of clothing day and night. Sleeping bags were provided and essential, as there was no heating. The first two nights, we stayed in basic, uninsulated accommodations.

Like most high-altitude deserts, the compact soil of the altiplano absorbs little heat from the sun, making nights extremely cold. With wind-chills, the temperature can drop as low as -25°C, resulting in some of the most extreme day-to-night temperature fluctuations in the world.

Day 1: Tupiza, Inca Ruins, and the Frozen Volcanic Formations of Ciudad del Encanto

From Tupiza, we headed through the stone ridges of Quebrada de Palala, sculpted by centuries of erosion, stopping at El Sillar, also known as the Valley of the Moon. We then continued to Ciudad del Encanto, a sprawling expanse of volcanic rock formations spanning several kilometers in diameter in the remote Sud Lípez province. The arid conditions here contribute to the stark, barren appearance of the land, which overpower the feeble signs of life and human activity, reduced to scattered patches.

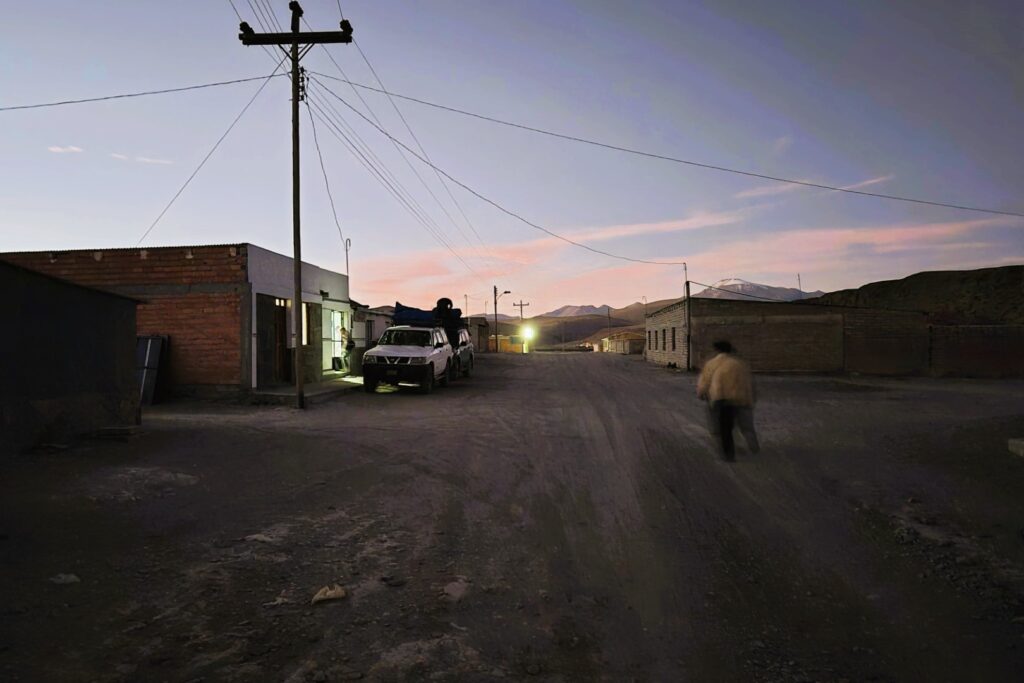

On our way, we passed through the small gold-mining communities of Nazarenito, San Pablo de Lípez and San Antonio de Lípez, before reaching Quetena Chico, a tiny desert town of just 400 residents, where we spent the night at the Lodge Andino Lamphaya.

The lodge appeared abandoned, but it had a nice living room with skylights, couches, and some magazines. The night proved bone-chilling due to a lack of heating, hot water, and the many gaps in the walls and windows. Outside, temperatures must have dropped to -15C, yet the view of the Milky Way made it worthwhile. Tucked in bed and buried under five or six heavy wool blankets, it took a good hour for my body heat to warm the sleeping bag.

Day 2: Desierto de Dalí, Volcanic Geysers, Half-Frozen Mineral-Stained Lakes Populated by Flamingos

The Eduardo Avaroa Andean Fauna Reserve is a huge protected area in Bolivia, covering 7,000 square kilometers at altitudes ranging between 4,000 and 6,000 meters. The landscape here is shaped by the wind and contrasts white salt flats with dark ochre and black mountains. Located at the southern edge of Bolivia near the Chilean border, the reserve is remote, with its southern limit several days’ travel from the nearest Bolivian city. Here stands the dormant volcano of Licancabur, which rises to an elevation of 5,868 meters.

Our first stops were Laguna Kollpa, a lake known for its large deposits of raw materials used in soap making, and Laguna Verde sitting 4,250 meters above sea level in Bolivia’s southeast corner. The green lake’s color changes from turquoise to emerald, depending on how much the wind stirs up the arsenic and magnesium sediments in suspension.

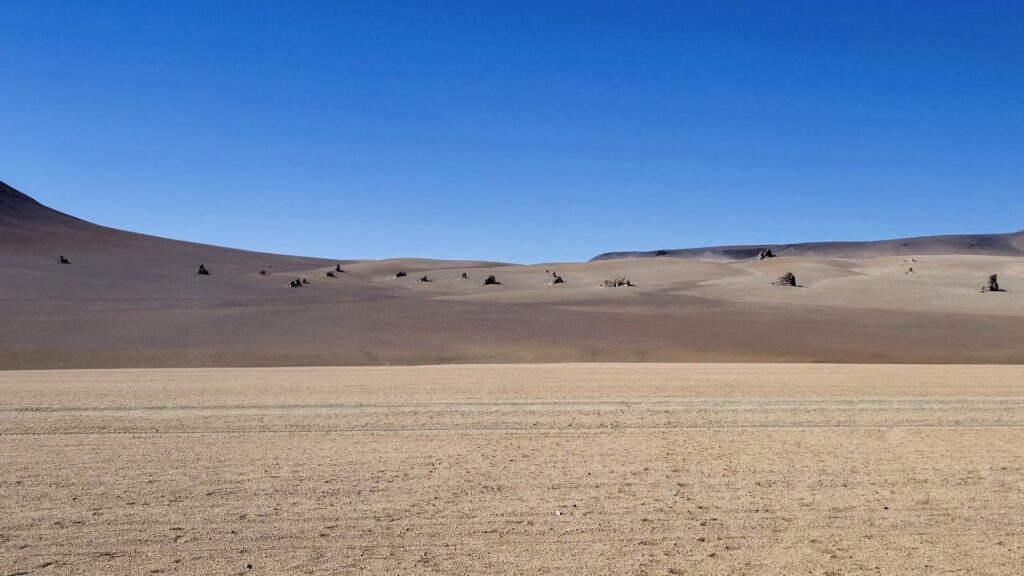

Next, we explored the Desierto de Dalí, a surreal desert landscape with colorful mountains and solitary monoliths that appear like mirages on a flat desert surface. These rock sentinels are the remnants of molten lava that were solidified and scattered across the terrain by the artistry of random patterns.

At Salar de Chalviri, we took a break from the chill and altitude sickness while dipping into natural hot springs filled with volcanic water at a perfect 37°C, with very uncomfortable transition between the pool and the outside.

In the afternoon, we visited the bubbling pools of mud and sulfur of Sol de Mañana Geysers, located at an altitude of 5,000 meters. These geysers send jets of steam into the air early in the day, but their energy fades as the hours pass.

Laguna Colorada is the reserve’s largest lake, with unusual hues of red, white and pink. The red comes from a natural pigment present in the algae, while the white edges are due to ice and borax deposits, a mineral used in the fabrication of paint and glass. The pink is from the hundreds of flamingos splashing in the icy shallows in search of crustaceans and algae.

Remarkably, three of the world’s six flamingo species gather here, so there must be something worthwhile. These birds are equipped with a clever system in their beaks that filter food from the toxic water, moving water in and out quickly like a piston to catch the edible particles while avoiding harmful substances.

The park office tower has a pleasant café where we warmed up briefly, but nights here can get brutally cold, dropping below -20°C.

Despite the harsh conditions, tenacious ecosystems survive around the salt flat’s arid margins, including colonies of cacti, hardy plants, viscachas (a rabbit-like animal). Aymara and Quechua communities live here too, scraping by in this tough environment.

We spent our second night in the small village of Villamar, where the accommodations were basic. I managed to borrow a heater for ten minutes: a short luxury to avoid cutting off the power for everyone else!

Day 3: Italia Perdida, Cañón de la Anaconda, Villa Candelaria

On the third day, we visited Italia Perdida and Valle de Rocas, known for their geological artistry. Among these is El Camello, a mythical camel said to have been turned to stone by ancient deities for wandering through the valley. Geoglyphs carved into the ground by early inhabitants are said to be visible from higher vantage points. The Cañón de la Anaconda, named for its snake-like curves and green coloration, hosts unique plant species that have adapted to its particular microclimate.

We ended our day with a stay at Villa Candelaria in a hotel made of salt, a historic stop for traders between Bolivia and neighboring countries, for another freezing night.

Day 4: Isla Incahuasi, Salar de Uyuni, Cementerio de Trenes

Our journey to the Salar de Uyuni began before dawn—at 5 in the morning to be precise—to catch the night stars over the world’s largest salt flat. Situated at an altitude of 3,650 meters, the Salar sits lower than the rest of the Altiplano. Thanks to this drop in elevation, we enjoyed a slightly less freezing climate.

As the first light of day began painting the horizon, we drove 60 km across the Salar to Incahuasi island, one of the many small islands scattered across the white expanse. Watching the sun rise over the plain from this icy island was a surreal experience and one of the highlights of the trip. Incahuasi is a geological oddity: rocky outcrop covered in fossilized algae, where giant cacti, some growing over 9 meters tall, thrive and are believed to be hundreds of years old.

Early in the year, these cacti bloom with bright white flowers, drawing the attention of giant hummingbirds. The trunks of the cacti are the only source of timber in the area, used for building doors and roofs in the surrounding settlements. The island is also home to lost viscachas, small rabbit-like rodents that survive on the sparse vegetation, forever trapped in a bleak habitat, encircled by white desolation.

The vast white expanse of the Salar stretches over 12,000 square kilometers, creating a surreal, convex terrain. The ground beneath us was made up of 11 layers of salt, ranging from 2 to 10 meters thick. Beneath these layers, the salt extends to a depth of 120 meters, forming the planet’s largest reserve of lithium, magnesium, potassium, nitrogen, phosphorus, and borax. Learn more about the unique geology of the salt flats here.

The journey ended 3 kilometers southwest of the town of Uyuni, at the eerie train cemetery. It’s another strange topography, shaped by the metal carcasses of former train parts, now surrendered to natural decay, slowly rusting and blending back into the landscape.

Intriguing flora and fauna

The trip back to Tupiza through the main road was equally fantastic

What to know

Tour costs are similar across operators, and all have faced issues in the past, including fatal accidents. The itinerary can change due to the weather, so you have little control over it. We had our own cook, who prepared excellent meals for lunch and dinner, which isn’t standard for all tours. Rarely do meals on a tour rank as some of the best I’ve had.

- Cost (for 4 days): 1250-1350 Bs (approx. CAD $260, about CAD $66 per day), depending on group size (4 or 5 persons plus driver)

- Park Entry Fee: 150 Bs (approx. CAD $30)

Cost includes:

- Transportation in a 4×4 vehicle.

- Driver who doubles as a guide. English-speaking guide at extra cost.

- Dedicated cook who prepares meals (it could also be the driver depending on companies). Expect high-sugar food imitation for breakfast.

- Basic accommodations and sleeping bag.

- The possibility of a free return trip to Tupiza, where you can retrieve any stored luggage.

What to expect

- Extreme winds, enough to blow my glasses away as I stepped out of the car (luckily, I found them!).

- Extreme temperatures, dropping well below -15°C at night.

- No heating or hot water, and therefore no way of getting warmer (you can pay for a hot water shower when available). You’ll only rely on the sleeping bag to conserve heat.

- Average elevation of 4,000 m, reaching 5,000 m, with peaks up to 6,000 m.

- Salar de Uyuni facts: The salt flats sit at an altitude of 3,653 m, span a diameter of 100 km, and have a dept of 120 m. They are the lowest and warmest place of the trip.

- Rough travel, due to the absence of roads on most of the trip.

- Again, sub-zero temperatures at night with no way of getting warm: on the positive side, you’ll be so exhausted from the days travel that falling asleep shouldn’t be a problem.

- If the flamingos chose this place to hand out, there must be something worthwhile!

- Building on the salt flats is illegal.