Costa Rica is overdone, overpriced, and overrated. Still, you need to go, if only to visit these two spots: the Caribbean coast around Puerto Viejo and the cloud forest of Monteverde. One has plants of laid-back paradise beach you can reach by bike. The other is a cool little tourist town set high in the clouds.

July is a good time to visit as it is the low season. Fewer crowds, better deals without reservation. Yes, it rains, but not all day. And the showers bring cooler air and dramatic skies.

Puerto Viejo & the Caribbean Coast

Puerto Viejo de Talamanca is far enough from the main tourist circuit that it still feels like a place where people live, not just visit. It’s also where many expats settle, naturally. For the car-free nomads out there, it’s perfect. The flat coastline from Cahuita to Manzanillo is easily reachable by a frequent public bus or by renting a bike—the old-school kind with pedal brakes—available from the many rental shops.

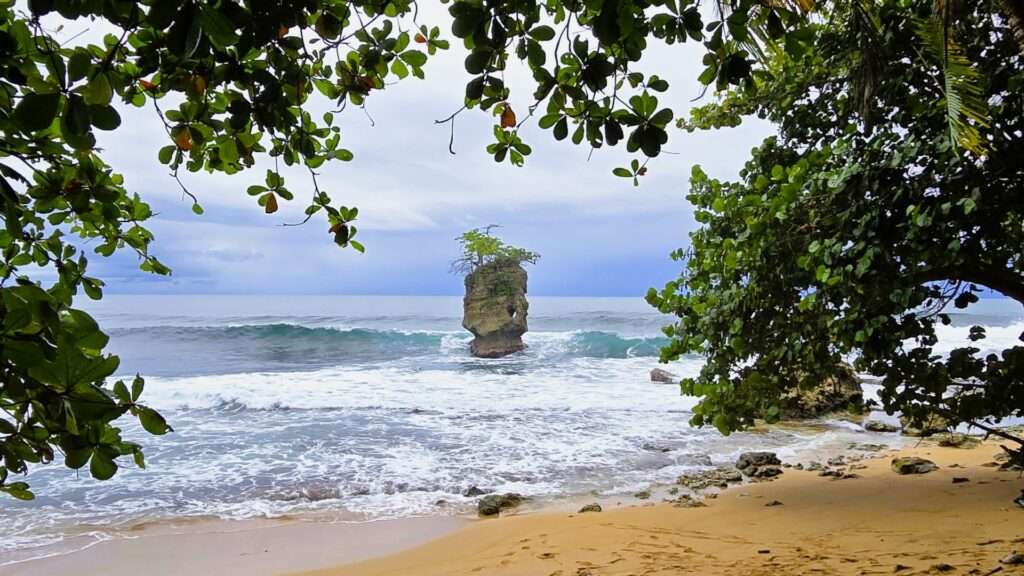

No matter how you travel, you’ll sometimes catch stretches of beach from the main road; other times you’ll be surrounded by cathedral-like forest, and occasionally you’ll find paths cutting through it. Then comes the best part: taking one of those paths through the thick, fairy-tale jungle until it suddenly opens onto a deserted, postcard-perfect shore.

The crown jewel are, the two protected natural areas (Cahuita National Park and the Gandoca–Manzanillo Wildlife Refuge) cost around 2-3$ to access (on donation) and offer some of the most pristine mix of beach and jungle scenery you’ll ever find on earth.

The weather is fully tropical, but the ocean breeze, porous ground, and lack of pollution make it surprisingly bearable, even without AC at night.

Monteverde & The Mystical Forest

Monteverde Reserve sits squarely on Costa Rica’s tourist path—along with Manuel Antonio National Park, just a few hours outside San José. Monteverde and Santa Elena are perfectly curated mountain towns built for vacationers with more money than time. As a solo traveler, you may feel out of place dodging families and groups moving in and out like it’s a Disneyland turnstile.

It’s also car-only territory. Without your own wheels, your tired legs won’t get you far. There’s no public bus, and the only alternatives are oversized 4×4 taxis built to shuttle large families around. So much for sustainability. On top of that, most of the nature here is either fenced off on private property or behind ticket booths with entry prices hovering above $20 USD. Finding something to do that doesn’t empty your wallet can be tricky.

That said, as a car-free nomad, you can still have a good time. The town of Santa Elena, which holds the bus terminal and most amenities, thrives on tourism, so you’ll find accommodations for every budget, plus cozy cafés designed for remote work (something lacking in San José) and plenty of gift shops selling carved wooden cups and sloth T-shirts.

The town itself is charming, the air is fresh, and mist often drifts through like a natural fog machine. You can spot funky cloud formations and spectacular sunsets if you stretch your neck a little.

Here, the sunlight kills the mood. I had been waiting for a foggy day since I got here, and was lucky to catch a good 45 minutes of it before the rain came pouring down.

Animal Encounters Without Even Trying

I watched a band of mantled howler monkeys cross the hostel’s backyard, laboriously leaping from one fan palm to another. These monkeys never touch the ground, preferring to spend their days resting on branches high in the jungle canopy, feeding on leaves, fruits, and flowers. Humans don’t interest them, nor does our food. At dawn and dusk, you can hear their eerie calls from kilometers away: it’s the males delimiting their territory.

Coatis look like a cross between a raccoon and an anteater, with long noses, sharp claws, and ringed tails. Females and young live in groups, while males walk alone. They eat just about anything—fruit, insects, small animals, and scraps. Curious and bold, they often search for food near people, sniffing around bags at campsites and along trails.

Sloths (perezosos) spend nearly their entire lives hanging upside down in trees. Algae grows on their fur, giving them a greenish tint that works as camouflage. They eat mostly leaves, which are tough to digest and provide little energy—hence their slow pace and long naps. They only come down to the ground about once a week to poop, a risky ritual that makes them vulnerable to predators.

Hermit crabs (bernard-l’ermite) are common along Costa Rica’s beaches, skittering across the sand. They don’t grow their own shells, but instead use empty snail shells, swapping them out as they grow larger. This creates constant competition for the best fit. They feed on anything left behind by the tide: algae, bits of plants, or dead fish. Watching them cluster around food, dragging their borrowed homes with them, feels like witnessing a miniature society at work.